|

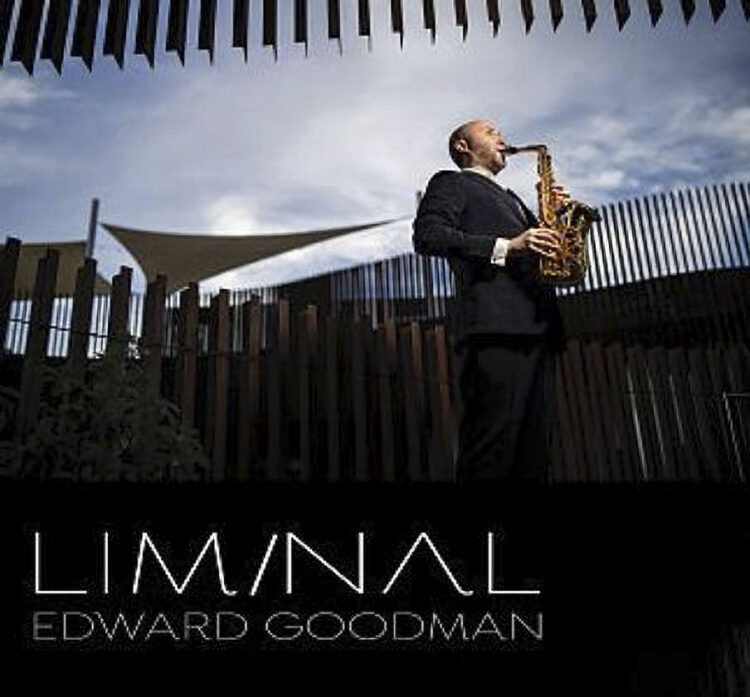

FANFARE MAGAZINE LIMINAL • Edward Goodman (sax); Liz Ames1 (pn) • SOUNDSET 1119 (72:50) |

|

JOHN ANTHONY LENNON 1 Distances Within Me. TOWER Wings. BOLCOM 1Lilith. ASIA The Jane Set. BOULEZ Dialogue de l’ambre double |

It is not every day that one comes across a piece of music written after Lilith, the first wife of Adam in medieval Talmudic lore, and created of the same clay. She is an active current in occultism today, though, a symbol of the Divine Feminine, a dark feminine architype celebrated by modern occultists such as Asenath Mason and the magicians of the Temple of Ascending Flame and, possibly most famously in recent times, Donald Tyson in his “gnostic grimoire” Liber Lilith (Starfire, London, 2015). Anyone attempting to capture Lilith in sound, if these august writers are to be believed, needs a constitution of steel; Mason, amusingly, refers to Lilith as “The Queen of the Night” (nicely linking into our musical theme here) while referring to her in her capacity of “mother of demons” and the “source of all evil and pollution in the world” (Tree of Qliphoth, Temple of the Ascending Flame, 2016, pp. 13/14). It’s not a reputation that put off William Bolcom, who in 1984 penned a five-movement piece that explores her various aspects: “The Female Demon”; “Succuba”; “Will-o’the’Wisp”; “Child Stealer”; “The Night Dance.” Indeed, stealing children is one of the actions Lilith is most famous for, while Tyson’s book focuses more on her sexual aspect (she appears in dreams to seduce men and drain them, allegedly something once experienced leads one back for more and more of the same; hence the “Succuba” movement). Tyson’s book, ostensibly fiction, achieved some notoriety at one point as he gives instructions on how to contact and work with Lilith; there existed an internet blog of a gentleman who attempted it (the instructions are far from easy and, indeed, remarkably demeaning) which simply tailed off at a crucial point….

There’s no doubting the visceral screams, separated by silences, in Bolcom’s “Child Stealer” movement, probably the clearest depiction of Lilith’s essence here. Interestingly, “The Female Demon,” the first movement, has real beauty to it as well as angularity, the sax almost transmuting into a snake charmer. The use of an E♭ alto saxophone gives it a particularly wild character, to my ears. The movement moves from the seductive to the blood-red raw. Pitting quiet, seemingly harmless piano chords against more menacing gestures in the sax, “Succuba” acts in contrast to the dark flickerings of “Will-o’-the-Wisp,” superbly performed here (particularly the piano contribution of Liz Ames). The composer himself says that the work “explores her [Lilith’s] life in the wilderness, with music at turns seductive and frightening.” He also acknowledges the wide range of multiphonics he asks for, all flawlessly delivered by Edward Goodman. This is, without doubt, as great a piece of music as it is fascinating. His pianist, Liz Ames, is a supreme partner (as opposed to “accompanist”); one can hear the thought that has gone into her participation.

The other piece with piano is the first on the program, John Anthony Lennon’s Distances Within Me (1980), a piece that references Alban Berg as easily as it does Weather Report and Jimi Hendrix. An evolving rondo, in that material may return but always as part of a journey of continuing transformation, Lennon’s piece immediately links in to the title of the album, Liminal; spaces between one place and the other (given that we have had Lilith, maybe we should also have Hekate, the dark Keeper of the Crossroads and other liminal spaces, too?). The musical mode of discourse from Lennon is very different from Bolcom. As Lennon puts it, “the aesthetic is from popular culture and not from the world of classical music. For me, writing Distances Within Me was a break from the restraints of aging modernism.” It is far from an easy piece though, requiring fine timing between the instruments (Goodman and Ames seem to be absolutely of one mind). There is certainly a sense of flow audible; Lennon wrote the music first and added bar lines later, which seems eminently believable.

The balance of the program is for solo sax. Joan Tower’s Wings (1981) was originally for solo B♭ clarinet but was transcribed by the composer in 1991 for alto sax at the request of John Sampen. It is a depiction in sound of a large bird, like a falcon, in flight. Goodman worked personally with Tower during her residency at the University of Arizona in 2017, so this reading enjoys a measure of authority; it also allowed Goodman to follow his intuition to revel in the music’s virtuosity.

I have reviewed a number of releases by Daniel Asia in the past for Fanfare, and always positively. His The Jane Set (2012, one of a series of “sets”) speaks of a deep lyricism, and one that clearly inspires Goodman. Although there is a crescendo of speed towards the third movement Vivace, even that has a sense of calm around it. It is Pierre Boulez who has the last word, though, with his Dialogue de l’ombre double (Dialogue of the Double Shadow, 1985), another piece originally for solo clarinet. The performance is best experienced on headphones, as the disc uses a panning effect, moving sounds from left to right in order to emulate spatialization (although on headphones one does become more aware of key click); it also uses playback of pre-recorded material by the performer. This is far from a single-person undertaking; Goodman was aided and abetted by the sound engineer Dave Schall, and also Wiley Ross from the University of Arizona. Boulez conjures up some absolutely magical sonorities in a work of absolute genius.

In short, this is a diabolically brilliant, wide-ranging program, superbly performed by two very special performers.

Colin Clarke