-

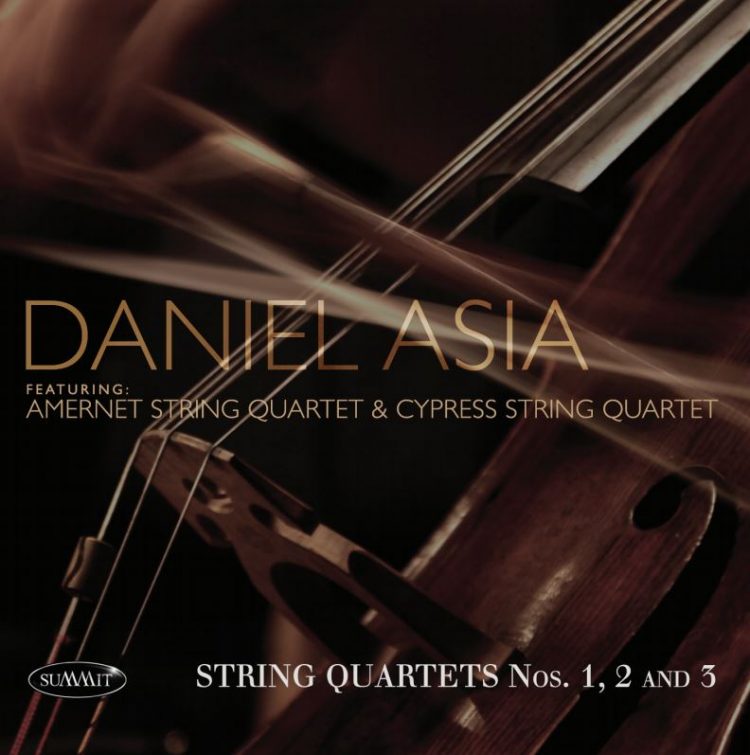

String Quartet No. 1: 1. Intensivo

1 -

String Quartet No. 1: 2. Dramatico

2 -

String Quartet No. 1: 3. Allegro

3 -

String Quartet No. 1: 4. Lirico

4 -

String Quartet No. 1: 5. Misterioso

5 -

String Quartet No. 2: 1. Cantabile, free and flowing- crisp & energetic-presto

6 -

String Quartet No. 2: 2. Moderato-free-moderato

7 -

String Quartet No. 2: 3. Majestic-dancing-majestic

8 -

String Quartet No. 2: 4. Presto possible

9 -

String Quartet No. 3: 1. Vivace

10 -

String Quartet No. 3: 2. Andante, pensive

11 -

String Quartet No. 3: 3. Whimsical

12 -

String Quartet No. 3: 4. With humor

13 -

String Quartet No. 3: 5. Adagio, soulful

14 -

String Quartet No. 3: 6. Playful, cantabile

15 -

String Quartet No. 3: 7. Vivace

16

One of my composition teachers and mentors was Stephen Albert. When I told

him I was writing a string quartet-my first-he bellowed back at me “How can you

even think of writing a quartet after Bartok’s?!” I remember being taken aback,

thinking about it for a moment or two and then responding “Stephen, then how

can one possibly write symphonies after Beethoven or songs after Schubert or

piano music after Chopin and Liszt?! (I write this using exclamation points as

Stephen only spoke hyperbolically and thus my response had to be of the same

order of magnitude of intensity.) As I remember that stopped him in his tracks.

Because either the forms are filled up and there is no more to say in them, or

one concludes that they are still viable and pregnant with possibilities. Certainly

the string quar tet medium remained an important medium for expression

by composers at the end of the last century. Any list of them would include

Lutoslawski, Brown, Druckman, Ligeti, Wernick, Crumb, Rochberg, Corigliano,

Carter, Tower, Lerdahl, and Tsontakis, among others.

This CD is in some ways then a response to Stephen’s outburst, although maybe

mostly in jest. They are written over a time span of about thir ty years and thus

show a good amount of change and development in style during that time. If

most composers’ outputs can be divided into three regions- beginning, middle,

and ending- these three quartets fit nicely into each of those categories (unless

I live like Carter to 103, which would put me still in the muddle of the middle).

of today’s exceptional string quartets and are Ensemble-in-Residence at Florida

International University in Miami. Their sound has been called “complex” but

with an “old world flavor.” Strad Magazine described the Amernet as “…a group

of exceptional technical ability.” Earlier in their career, the Amernet won the gold

medal at the Tokyo International Music Competition before being named first

prize winners of the prestigious Banff International String Quar tet Competition.

Prior to their current position at Florida International University, the Amernet

held posts as Corbett String Quartet-in-Residence at Northern Kentucky

University and at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

Additionally, the ensemble served as the Ernst Stiefel Quar tet-in-Residence at

the Caramoor Center for the Arts.

In their 20 years on the concert stage, the four members of the San Francisco-based

Cypress String Quartet played thousands of concerts together

throughout North America, Europe, Asia and Latin America. Praised by

Gramophone for their “artistry of uncommon insight and cohesion,” and by the

NY Times for “tender, deeply expressive” interpretations, they recorded over

15 albums and are heard regularly on hundreds of radio stations throughout

the world. They have also been heard on the Netflix original series “House

of Cards,” and collaborated with leading artists ranging from Michael Franti of

Spearhead to modern dance companies.

The first is rather brash and direct: each of the movements is short and sweet

and together create a satisfying unified architecture, one that builds in tension to

a high point and then releases. The second, built from my piece Marimba Music

(for that instrument played with four mallets and going as low as the cello), is all

about variations, as I was eagerly developing my technique in this regard. The

third is the most extended and varied, with rather long movements juxtaposed

with very short, almost micro, movements.

String Quartet No. 1 (1975) was written while I was studying at the Yale

School of Music, although I wouldn’t consider it a student work. It won an intra-

school award but I can’t remember which it was. Then again, Ives said awards

are for sissies. I don’t know about that, but I am still happy that it was considered

a strong piece by my compositional mentors.

It was first performed by the Rymour Quartet, who were then the student

quartet- in-residence. The group performed the piece splendidly and made the

first recording. I later was colleagues with the group’s violist and found its first

violinist in the concertmaster’s chair when my piano concerto was performed

in Chattanooga.

The work is in five moments almost all played without pause. The voice is

energetic and exploratory in its quick alternations of the macabre and frightening,

the quiet and serene, the rhythmically intense and gently lyrical. Architecture is

clear, with graceful and satisfying changes of intensity. The full resources of the

instruments are used, as the strings are bowed, plucked, and scraped, the bodies

of the instruments are rapped and tapped, and the bow is used both normally

and with the wood striking or being slid across the strings.

String Quartet No. 2 (1985) is a set of variations based on a three-par t theme.

The variations are gathered together in four movements, each with its own

shape and mood, although cross references and relationships abound.

The first movement presents the theme and four variations. The general

character of these variations is improvisatory and probing. The final variation, a

presto, brings the first movement to a breathless finish.

The second movement, comprised of variations 5-7, is somewhat of a

continuation of the last variation of the previous movement. It moves quite

quickly in steady sixteenth notes and triplets (although with a bit of rubato). This

gives way to a collage cadenza; here the musical movement is again somewhat

hesitant and pondering. It is characterized by quick changes of mood, from

Award, a Guggeneheim Fellowship, MacDowell and Tanglewood Fellowships, a

DAAD Fellowship, Copland Fund grants, the NEA (four times) and Koussevitsky

Foundation, the Fromm Foundation, and numerous others. From 1991-1994

he was the Meet The Composer Composer-in-Residence of the Phoenix

Symphony, and from 1977-1995 Music Director of the New York-based

contemporary ensemble Musical Elements. Asia’s five symphonies have received

wide acclaim from live performance and their international recordings. Under a

Barlow Endowment for Music grant, he wrote a work for The Czech Nonet, the

longest continuously performing chamber ensemble on the planet. He recently

finished the opera, The Tin Angel, and Divine Madness: The Oratorio, after the

eponymous books by Paul Pines, his collaborator of for ty years. Daniel Asia is

also a conductor, educator, and writer. He is Professor of Composition, and head

of the Composition Department, at The University of Arizona Fred Fox School

of Music, Tucson, and is also the Director of the annual Music + Festival and

Coordinator of the American Culture and Ideas Initiative. The recorded works

of Daniel Asia may be heard on the labels of Summit, New World, and Albany.

For further information, visit www.danielasia.net.

Praised for their “intelligence” and “immensely satisfying” playing by the New

York Times, the Amernet String Quartet has garnered recognition as one

Movements Two, Four, and Six, can be heard in relation to each other, a

subsidiary stream in relationship to the ongoing larger structure. Two and

Four are almost palette cleansers and are song-like. While movements One

and Seven are deeply conversational, these are more transparent, and with a

clear sense of melody and accompaniment. Movement Six is the most extended

of the three, and usually presents the instruments in simultaneous pairings. It

is of a playful and singing nature, with a burbling rhythm that just about runs

throughout. At the same time, in its structure, and the similarity of its opening

and closing, it imitates the structure of the entire work.

This quartet accepts certain influences from popular music which are absorbed

into its more complex texture and language. The keen listener may hear the

very occasional shard of material that may remind of something heard from

a television show theme, or even the movie The Wizard of Oz. While these

associations don’t leap out, they are present, even if only on a subterranean

level. It is a way of raising the vernacular to the refined, the mundane to the

sacred, with the goal of creating a music of deep and true engagement.

Daniel Asia has been an eclectic and unique composer from the star t. He

recently received a Music Academy Award from the American Academy of Ar ts

Letters and has received grants from Meet the Composer, a UK Fulbright Arts

pensive, wispy, and atmospheric, to slightly mad! This section gives way to a

return of the sixteenth note motion of the opening variation, but always with a

degree of hesitancy.

The third movement is marked majestic and includes variation 8 and a dance-

like music that has the quality of a delicately distorted pavanne. These dance-

like sections always give way to the variation material. At the conclusion, a final

reference is made to the very first variation.

The final movement, formed entirely of variation 9, is based on variation 4,

which in turn is based on the thematic idea played in reverse. More importantly,

it is based on steady sixteenth-note motion in two groups of 3 and is played

as fast as possible. A middle section of a more quiet, keening music presents a

brief contrast before the quick-paced music returns. Seminal ideas of the theme

are heard, as all aspects of the work are drawn together as the work races to a

breathless conclusion.

The work, written in 1985 while I was living in Oberlin, was supported by a grant

from the Ohio State Ar ts Council.

When I first discussed the possibility of doing a String Quartet No. 3 (“The

Seer”) with the Cypress Quartet, we spoke of the implications of working with

their Call and Response series, and various possibilities of influences and works

to consider “ riffing off of ”. I concluded that it would be most interesting to

consider the ramifications of working in the context of Dvorak’s Op. 96, also

called the “American Quartet”. I was drawn to its musical landscape, but also by

the implications of Dvorak’s ties to the old world as well as his sojourns in the

new. It seems to me that an American composer lives very much in this place

and time, but is also strongly influenced by past associations and past music.

Being American, in many respects, means integrating multiple influences and

identities. Therefore, this quartet, like Dvorak’s and perhaps Ive’s, fuses various

influences.

Titles always come after the fact for me. While working on this piece, I visited

the Phillips Gallery in Washington D.C. I have always been drawn to the visual

arts, as they are another non-verbal means of expressing that which is deeper

than words can describe. There were qualities of Adolph Gottlieb’s painting

“The Seer” that seemed quite analogous to my quartet. The work is mosaic

like in its larger structure. Certain shapes or patterns run through the work

while others stand in isolation. Seemingly incongruous panels of shapes build

up a pleasing and articulate form which is complex and has multiple layers of

organization.

My quartet is structured somewhat similarly. Movements One and Seven are

constructed on similar materials yet have different processes of development.

The First engages its materials in a process of deconstruction and then

reconstitution, while the Seventh star ts almost hesitantly and in dissolution, and

gradually works its way towards unity and reconciliation. The music is highly

rhythmic, almost motoric, and explores quite angular shifts of register and

instrumentation.

Movements Three and Five are the other par ts of structural importance, but are

also quite independent of each other, or of movements One and Seven, for that

matter. Movement Three is whimsical and quixotic. Thus, it is full of rapid mood

swings, from its almost dance-like materials, to those which are of a breezy,

more superficial nature. Movement Five is an adagio, a slow and somber musical

utterance. It is clear and straight forward in almost all aspects, as its rhythms are

simple and plain, and its melodies sharply defined. The trajectory is defined by

register, as it star ts very low, rises to the heights, and at its conclusion, comes

to rest in the lowest register yet again. The climax of the movement is arrived

at somewhat suddenly, and sections of repose are also heard, providing textural

respites on the journey.